News

The Antipodean Alex

03/09/2022

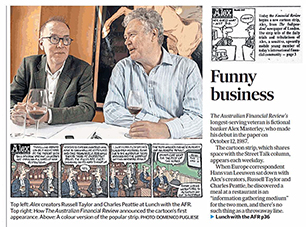

How Alex cartoon creators find the funny side of finance

by Hans van Leeuwen..

The creators of Alex are cartoonists not bankers, but they’re uncannily good at skewering the world of finance. What’s their secret sauce? The answer: lunch.

click here to read print version

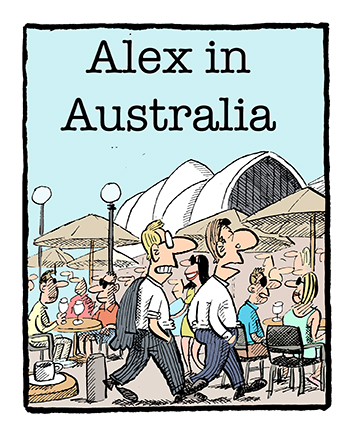

Who is The Australian Financial Review’s longest-serving veteran? It’s not John Davidson, even though he has been writing technology reviews since 1996; and it’s not editor-in-chief Michael Stutchbury, he wrote his first article in 1982, and he’s had a longish spell elsewhere. The paper’s oldest hand is actually fictional: his name is Alex Masterley. He is the pinstriped cartoon financier whose antics have for decades skewered the world of banking and broking, with often unnerving accuracy. He first appeared in the Financial Review on October 12, 1987 – half the newspaper’s seven-decade lifetime ago. Over the years of boom, bust, boom and bust again, he has grown older but probably no wiser, even if he is often less pinstriped. And through it all, the two men with the pen, Charles Peattie and Russell Taylor, have remained the same.

I’ve often wondered how they do it. The cartoon is uncanny in its feel for how finance works and how bankers think, and in its ability to keep up with the trends and water-cooler conversations in the City of London. Every day the pair somehow converts this financial and social acumen into a nifty joke. And not only that – the jokes are satirical, even cutting, but also offer an affectionate chronicle of corporate life. It’s no easy task to poke fun at people yet keep them onside. Business readers love it because they recognise its truth, but more importantly because they are parodied rather than pilloried.

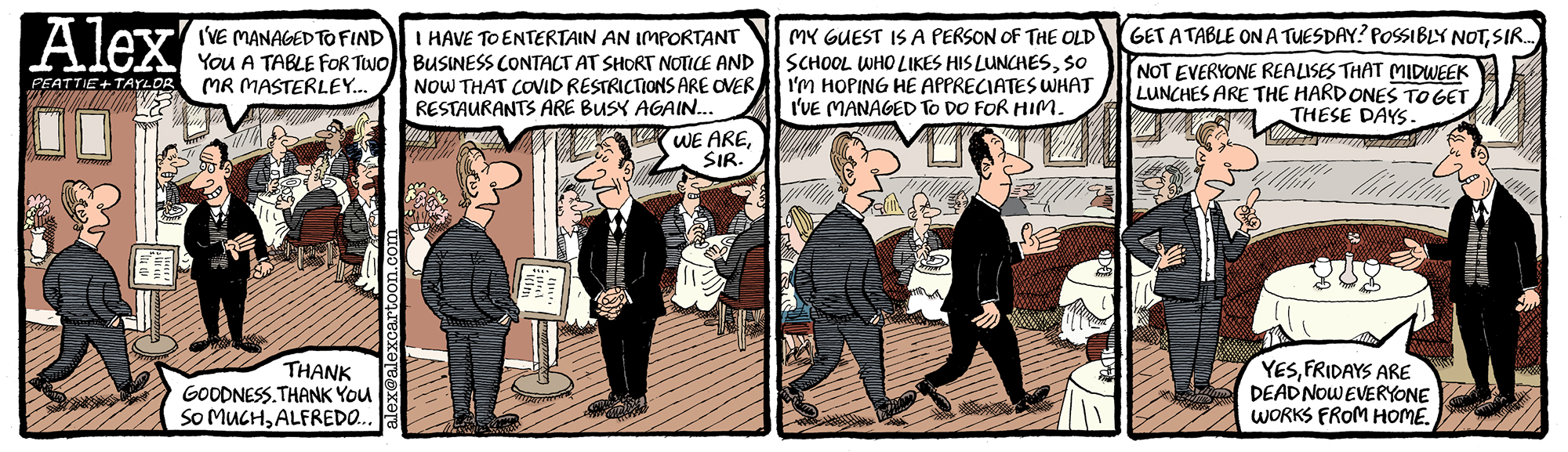

I’ve invited Taylor and Peattie to a double-bill lunch to discover their secret sauce. And before we even get to a table, I learn a lot about their modus operandi. Grist to the mill. Taylor and I exchange a few texts about dates, and we settle on a Friday. I say it was easy to get a table as everyone now works from home on Fridays, so Thursday is the new Friday. A couple of days later, I see an Alex cartoon that has pinched this idea and turned it into a joke. Like a journalist, which Taylor says he basically is, every conversation with the Alex creators is grist to their mill. Taylor suggests a couple of places that are famous lunch haunts of the City of London establishment. The reason? Peattie wants to sketch the interior, so it can form the backdrop of future Alex cartoons.

This cartoon was inspired by a throwaway line from Financial Review correspondent Hans van Leeuwen.It’s another clue that they take their humorous mission very seriously. The backgrounds aren’t highly detailed in an Alex cartoon, but they have to look real and recognisable. The waiter’s outfit, the shapes of tables and whether they have tablecloths on – this minutia matters for the cartoon’s credibility. We settle on the Bleeding Heart Bistro: an airy, tasteful, unshowy French-style place in the Hatton Garden jewellery district, just beyond London’s financial “square mile”. “A lot of City restaurants went bust or didn’t reopen after lockdown. This one sort of held up and has now become the last bastion of the lunches,” Taylor says as we sit down. He knows a lot about lunching. Peattie begins to make some sketches as Taylor talks. They’re both in their early to mid-60s, but you’d never know from their eagerness and energy. Taylor points out the head waiter to Peattie. “Charles, that’s what the maitre d’ looks like.” He turns to me. “They just wear a normal suit these days. Within the cartoon, waiters always wore black tie. Of course, they don’t anymore, so we had to update that.”

As expected, the restaurant is pretty quiet. “I should’ve got all my City guys come sit at tables and pretend to be impressed by how famous we are. But obviously, probably everyone’s at home on Friday,” Taylor says. It turns out he didn’t need to stage anything. The proprietor, New Zealand-born Robyn Wilson, comes over to say hello. She spends some of each year back home and knows the AFR Weekend. She’s excited to see Alex’s creators lunching. We chat to her about how the Bleeding Heart is going, post-lockdown. Taylor, who calls lunch “the information-gathering medium”, is making this intelligence-collection malarkey look pretty easy. His email signature block describes him as “writer and luncher”, but he peppers his conversation with references to lunching not being what it used to be. Not as lavish, not as louche, and not as liquid. The three of us, though, decide to cleave to tradition and order a bottle of wine “to make sure we get it right”. Less traditionally, Taylor and I are vegetarian. We order leek soup, he has a risotto and I go for aubergine tamarind. Peattie picks the more timeless options: fish soup and coq au vin. “I haven’t had coq au vin for so long, probably since the 1970s,” he says. At that point, they were still cheeky, private schoolboys. By the early 1980s, Peattie had been to art school, and was trying to make it as a portrait painter and cartoonist. Taylor studied Russian at Oxford and subsequently tried to set up a travel agency selling “real life” trips to the Soviet Union. It failed, but he managed to write a funny book about it, and ended up working in journalism.

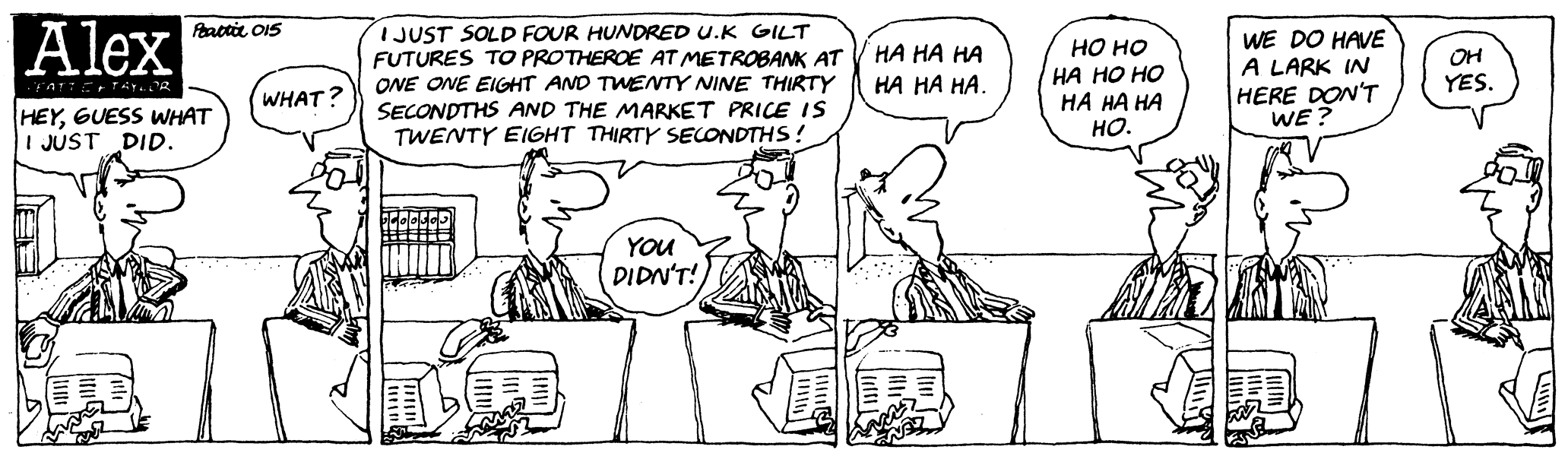

In early 1987, Peattie took his portfolio into the offices of the London Daily News, a start-up that was the brainchild of media mogul Robert Maxwell. The editors told him to come back with a London-themed cartoon of some kind. He needed a co-writer, and when he met Taylor things seemed to click. Neither of them knew much about finance, but it was the mid-1980s and Margaret Thatcher’s “big bang” financial reforms had left London crawling with a breed of brash, young bankers: the yuppies. “In the early 1980s, it was all about people being very right-on and left-wing and hating Thatcher. And then came along these people who wanted to show off and have lots of money and be insensitive, and that seemed very funny to us,” Taylor says.

The strip seemed to work, most particularly with the people it sought to satirise. “They loved it,” Taylor says. “There wasn’t really anything else for them,” Peattie chimes in. The pair either complete or elaborate on each other’s thoughts, which is unsurprising after 35 years of collaboration. I’m almost surprised they don’t taste each other’s soup. These days they tend to speak on the phone just a few times a week. In the early days they worked in a little office in the Docklands, where they began getting frequent visits from City types wanting to set them straight on how best to portray Alex. Taylor says one source boasted to him about taking a flight from London to Zurich via Helsinki, just to make the flight last more than four hours, so he could go business class. “I said, ‘if you tell me this stuff, I’ll put it in a cartoon and your boss will read it’. He said, ‘that’s the point – we want him to know how clever we’ve been, and then we’ll think of something cleverer,’” Taylor says.

The enthusiasm of the audience gave the strip a life of its own. When the London Daily News folded, the strip moved to the Independent, then to the Daily Telegraph, its home since the early 1990s. It has run continuously through the 1987 crash, the 1990s recession, the tech boom and bust, the global financial crisis, the rise of crypto, the pandemic, and on it goes. “We like change. Just when you get sick of all the jokes about bonuses, you can get a lot of jokes about being fired. Boom-bust economics is good for Alex,” Taylor says.

The first strip that appeared in the Financial Review on 12th October 1987The AFR took Alex on about eight months after it started. To this day, the authors wonder what Aussie readers make of it. Do we see Alex as one of us, or do we see him as a slightly unrelatable Brit? We chew it over as we eat our mains – simple but tasty, the food abets conversation rather than distracting from it. “Australians have got the same sense of humour – that irony and sarcasm,” Peattie says. Taylor adds: “The Aussies have got that American upfrontness, but with a British sense of humour. It’s a great combination.” Peattie went to Australia in 2008 to attend the premiere of a play based on Alex, at the Sydney Opera House. Lehman Brothers collapsed while he was on the 24-hour flight. “It was on the news, on the backs of our seats. By chance I was sitting next to two Lehman bankers and they were going, ‘ooh that looks quite serious’. By the time we landed, everybody thought it was the end of civilisation,” Peattie says. Peattie spent much of the trip in his hotel room, exchanging joke ideas with Taylor by email. “When things are going wrong, that’s the best for us,” he says.

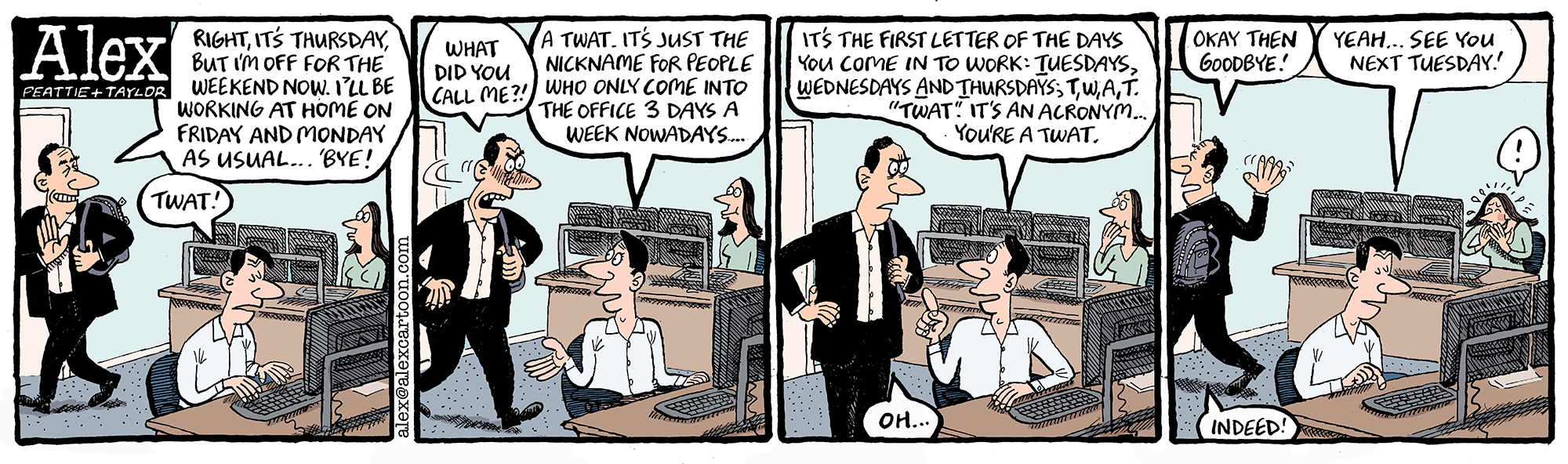

For the past couple of years, they’ve been poking fun at the working-from-home phenomenon in forensic fashion. Another theme has been the culture clash between the City’s old-timers and the aspirational Millennial/Gen-Z generations who have joined the workforce. Alex, like his creators, isn’t getting any younger. “We did make the decision to age the characters in real time, not like Charlie Brown who was perpetually nine years old,” says Taylor. “We slightly regret that now that our characters are a bit too old to work in finance.” So will Alex have to retire? Peattie: “He’s never going to reach retirement age.” Taylor: “Those guys never retire. They end up in headhunting, or private client wealth management.” And will Taylor and Peattie have to retire? “We’ll get sacked, we’re not going to retire,” Peattie says. Taylor: “All City guys keep going until they get taken out and shot. Alex wouldn’t want to retire, and we cannot afford for him to retire.”

Peattie & Taylor nominated this as a particular favourite.